Forensic DNA analysis is often used to solve crimes, but have you ever wondered how a DNA profile is detected?

By: Christabelle Lim

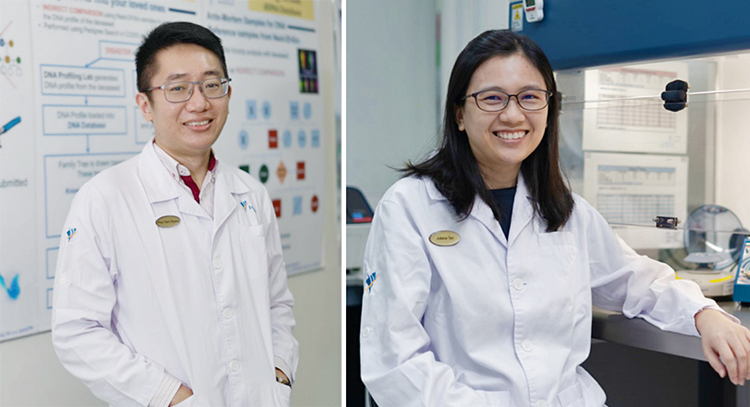

Mr Ryan Ping and Ms Jolena Tan are Senior Forensic Scientists at the Health Sciences Authority, specialising in forensic DNA analysis and serology. Police Life speaks to them to find out what a typical day is like in the DNA forensic laboratory, the challenges they face and the team effort required to translate new research methods for use in the criminal justice system.

What’s the day-to-day work like in the DNA Profiling Laboratory?

Ryan: The bulk of our work involves supervising exhibit examination, interpreting DNA profiles, writing case reports and giving testimony in Court as expert witnesses. Although the lab work can be routine, every crime case is dynamic.

We also conduct research into new technologies to enhance and expand the forensic genetics capabilities of the lab as well as conduct training for police and judicial officers on the use of DNA evidence.

How does the work in a forensic DNA lab differ from an academic setting?

Ryan: They are similar in that we test and evaluate hypotheses. However, the difference is that the samples used in academic labs are usually high-quality, pristine and not limiting, while the samples in forensic labs usually contain environmental contaminants and are of limited quantity.

Forensic labs also don’t have the luxury of experimentation and must work within defined operating processes and limited samples.

What are some of the challenges faced by scientists in a forensic DNA lab?

Jolena: DNA profiles are getting more complex. This is because DNA testing methods and instrumentation are now highly sensitive and can pick up even low amounts of DNA. It can be a challenge to distinguish the many different contributors in a sample.

That’s why good evidence recognition plays an important role in crime-solving. Evidence triaging, coming up with the right questions, filtering what is critical to the case, all help ensure that laboratory resources are optimised.

How does the trend towards use of portable rapid DNA instruments, driven by the demand for faster DNA analysis, impact the work in forensic labs? Will forensic labs even be needed in the future?

Jolena: The rapid DNA instruments are fast, easy to use and can deliver results in 90 minutes. They are intended for use on pristine samples and can be performed by non-lab personnel with minimal human intervention.

In countries where a sample may take a long time to reach the lab, law enforcement officers can use such instruments to quickly obtain a DNA profile of a suspect via a swab and compare it to a database.

However, DNA collected from crime scenes are usually low in quantity and purity and may even be a mix from several different persons. Hence, it’s necessary to conduct the DNA processing in the laboratory, where trained personnel can analyse and interpret the results.

Crime scene investigations on TV often depict solving a crime is only a matter of conducting a DNA test. How true is that?

Jolena: The forensic DNA field has advanced rapidly over the past few decades; however, it takes time to translate new technologies into forensic use. For example, the age of a contributor can be predicted using DNA, but this currently requires a large amount of starting DNA.

Secondly, vigorous testing is needed to assess the robustness, reproducibility, reliability, and limitations of new methodologies and technology platforms to ensure they are suitable for forensic use.

The truth is that it takes a team to bring an offender to justice, from the investigators working the case and lab personnel processing the evidence to those in the legal system as well!

What’s the most memorable moment in your career thus far?

Ryan: It would be the sense of fulfilment that I felt as the lead scientist when the Y-chromosome DNA testing capability (to enhance male detection in sexual assault cases) was successfully implemented in 2018.

Jolena: It’s the sense of achievement that I get when the investigators informed us that the DNA leads which we’d tirelessly ploughed through had enabled them to solve a case!

Two Cases Where Forensic DNA Analysis Brought Criminals to Justice

The dead tell no tales, but what if there isn’t even a body? The 2016 Marina Bay Gardens murder case was solved using mitochondrial DNA sequencing for the first time in Singapore.

A gruesome find of chopped up body parts, and a silent witness, DNA. In 2005, various body parts were found along the Kallang riverbank. With the help of the silent witness DNA, the accused wasn’t able to deny his crime any longer. Superintendent Roy Lim, Head of the Special Investigation Section, recounts how officers ensured that justice was served.

Read Explainer: In the Lab for an exclusive look into the DNA laboratory process!